As per usual, I'm terribly behind on the updates I promised (sorry!). So I'm sure you've been at the edge of your seat, wondering what the heck I was doing all the way over in Queensland, Australia!! ;)

Well wait no longer-- I've got nothing but time here in the Galapagos thanks to jet lag, missing luggage (stuck somewhere between Houston and here :/) and a terribly unsuccessful adventure around town for remaining gear (summed up by the common response: "es complicado"). SIGH.

Jokes aside (I know you weren't REALLY at the edge of your seat), I'm really excited to tell you about my time at the Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS). It has been a pipe dream of mine to visit AIMS for many years now and it was pretty surreal to finally make it a reality.

|

| MADE IT!!! |

AIMS is a leading center for marine science, including a jaw-droping Sea Simulator (SeaSim) facility, where there are a number of projects investigating the impact of temperature, light, pH, sediment and other types of stress on corals.

But what brought me here was the world-class coral core archive and facilities run by my collaborator Dr. Janice Lough. Janice is a leading expert in reading the history of coral growth written in their skeletons. These histories provide a window into the impacts of environmental stressors, such as temperature and acidification, on coral health. And because coral growth is tied to climate, these growth histories can also provide insight into past ocean conditions (particularly temperature).

Over the last few decades, Janice and her collaborators have collected samples from all over the Great Barrier Reef, Western Australia and a number of other key sites to investigate past climate and it's impacts on reefs from these growth histories. Their floor to ceiling cabinets filled with these coral samples are also an incredible archive and resource for the larger community. My first day in the lab left my head spinning with research possibilities (and thinking-- "when I grow up-- I want THIS" ;)).

|

| I died and went to coral archive heaven ;) |

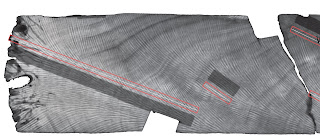

Coral growth is a function of both its extension upwards and the density of its skeleton. So to study coral growth, Janice and Neal Cantin have developed and refined two methods for measuring the density of the coral skeleton using x and gamma radiation. These methods work in similar ways. Like x-rays, gamma rays are high-energy photons produced during radioactive decay. We bombard the coral sample with x or gamma radiation and measure the amount that returns to the collector. The absorption of the radiation depends on the type of material, its thickness and....its density!

|

| X-ray image showing the seasonal density variations |

|

| Close up of the gamma density setup |

Which brings me to the more laborious, less glorious part of my work over the past ~month: measuring thickness! So what did I really do at AIMS? Many 'o hours turning the crank to drive a digital caliper, measuring thickness at 0.125 cm increments down the coral sample. So exhilarating that my first ever (5.8 magnitude) earthquake didn't even phase me. ;)

But from these meticulous measurements, I will produce robust estimates of coral growth in fossil corals from the Galapagos dated to the late 1700's!! Combined with modern Galapagos corals, these records will allow us to test the impact of ocean temperatures, pH, and other environmental conditions on coral growth at a site where corals experience strong variations in both climate and acidity from year to year. Will these historical fluctuations make corals from the Galapagos more or less susceptible to ocean warming and acidification? I hope to find out!